Astronomy: Dozens of the smallest asteroids found in the asteroid belt

Until now, only objects with a diameter of at least several hundred meters were known in the asteroid belt; most of them were too small. This is changing.

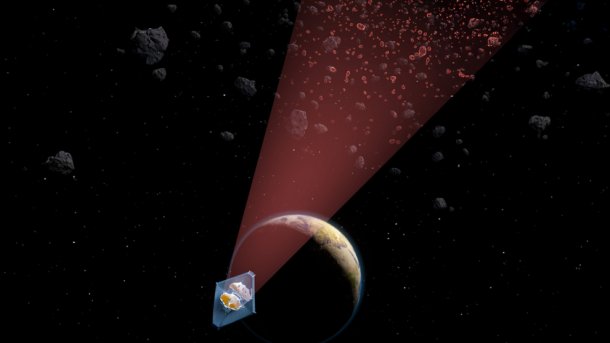

(Image: Ella Maru and Julien de Wit/MIT)

Using a new approach, an international research team has succeeded in discovering by far the smallest asteroids in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Some of them have a diameter of no more than ten meters, explains the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where the work was led. The team had actually hoped to discover a few new asteroids with their method, but ended up with 138, proving that such small celestial bodies can be detected not only when they are close to Earth. This is a great help in planetary defense, i.e. the defense against potentially dangerous asteroids on a collision course with Earth.

As the group explains, they used a technique for their search that is not new in astronomy. In this technique, numerous images of a narrow region of the sky are superimposed slightly offset in order to make traces of previously unknown celestial bodies visible in the noise. With the help of powerful graphics processors, which has only now become possible, the research team has applied this procedure to images taken of the star TRAPPIST-1 with the James Webb space telescope. This star is of particular interest because of its exoplanets. Because more than 10,000 images were taken of it, there was an enormous treasure trove of data to try out the procedure. And it paid off.

Videos by heise

The group discovered a total of 139 comparatively small asteroids, some of which are just the size of a conventional bus. In total, many more were discovered than originally hoped for. The method could now be used to detect a whole new population of asteroids and develop statistical models for the distribution of sizes. According to study leader Artem Burdanov from MIT, this opens up a completely new area of research in astronomy and shows once again what the research community can achieve when data that has already been collected is looked at in a different way. The work and the discovery are now presented in the scientific journal Nature.

(mho)