AI desktop in Anthropic's browser: designing applications with prompts

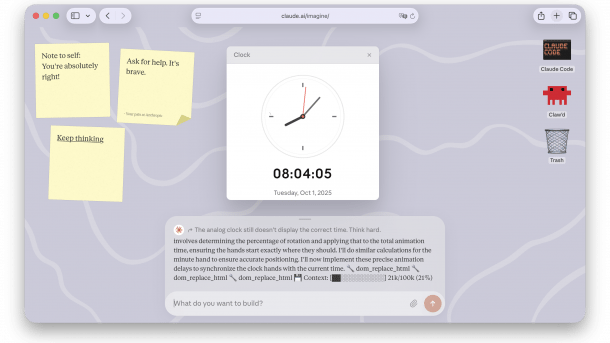

Anthropic is opening Imagine with Claude for five days: a desktop in the browser that can be customised with prompts, including your own programs running on it.

(Image: heise medien)

- Stefan Wintermeyer

The AI start-up Anthropic not only released its Claude Sonnet 4.5 model this week, but also presented an experimental feature: Imagine with Claude. Users can redesign the virtual desktop environment via AI chat and create applications on it using text input alone – Software that is created the moment it is needed instead of being programmed in advance.

The technology preview only runs for five days and is only available to paying subscribers of Claude Max. For everyone else, there is only a video on YouTube:

Empfohlener redaktioneller Inhalt

Mit Ihrer Zustimmung wird hier ein externes YouTube-Video (Google Ireland Limited) geladen.

Ich bin damit einverstanden, dass mir externe Inhalte angezeigt werden. Damit können personenbezogene Daten an Drittplattformen (Google Ireland Limited) übermittelt werden. Mehr dazu in unserer Datenschutzerklärung.

Anthropic itself describes the whole thing as a feasibility study. Nevertheless, it already shows what AI-supported software development could look like in the future.

Software out of nowhere

Once activated, a browser-based desktop interface opens with icons, windows, and a recycle bin. Any input can lead to the spontaneous creation of an application. Unlike traditional tools, functions are not ready-made, but Claude generates the necessary code with every interaction. The AI knows that it is controlling a website, but initially knows no details about its content.

The input field is located at the bottom. On the command "Remove the yellow notes from the desktop", Claude displays its internal considerations while working, searches for possible selectors and then deletes the notes.

The user wants to remove yellow notes from the desktop. I need to look for elements that represent yellow notes/sticky notes on the desktop and remove them.

However, I don't have any information about the current state of the DOM or what elements exist on the desktop. The user is asking me to remove something, but I need to know what selector to use.

Since this is the first interaction and I don't have context about what's on the screen, I should ask for clarification or try common selectors for note elements. But the instruction says "Answer the user's request using the relevant tool(s)" – so I should try to remove elements that might be yellow notes.

Common selectors for notes might be: – Elements with class "note" or "sticky-note" or "yellow-note" – Elements with id containing "note" – Elements with specific background colors

But I don't actually know what's on the screen. The user said "Remove the yellow notes from the desktop" – this implies there ARE yellow notes currently visible that they want removed.

Since I don't have the current DOM state, I should try common selectors. Let me try: – .note (common class name) –.sticky-note – [class*="note"]

Actually, looking at the system prompt again – it says the user is seeing HTML progressively and I'm reacting to their actions. This suggests there might already be content on the page that I created or that exists.

Since I don't have visibility into what's currently on screen, I'll try to remove elements with common note-related selectors. If they don't exist, the tool will simply not find anything to remove.

Let me try removing elements with class "note" or similar. dom_remove dom_remove dom_remove Done Context: ["░░░░░░░░░░░] 15k/100k (15%)

However, this does not always work so well. If you repeat the test with a fresh desktop, the AI sometimes fails at this comparatively simple task.

The available context is also limited with 100k tokens. If the memory is full, only a restart under claude.ai/imagine will help. In the next attempt, a terminal window can be opened with "Open a terminal", in which commands such as ls work. Files and directories are not real, instead Imagine generates them dynamically – including display in the Finder. Claude simulates the complete desktop system. If you create, change or delete a file in the terminal window, you can see the effects of these commands in the Finder window at the same time.

Another example: When you enter "Create a database with the lottery numbers of the last 10 years", Claude automatically starts an Internet search and collects the data to display it in a new application. With prompt inputs, you can extend this application with feature requests such as "Show the most drawn numbers". When you click on elements of the application, Claude considers how the application reacts to this click and then displays this. Different applications can exchange data within the same context.

Bugs arise and users have to fix them with new prompts. I was able to create a digital clock with one prompt. An analog clock needed three more inputs before it worked.

This is made possible by Claude Sonnet 4.5 in combination with agent-based control of the UI. A toolbox with commands such as WINDOW NEW or DOM REPLACE HTML works in the background. Claude generates and tests code in a sandbox-like environment to implement the desired functionality. This results in noticeable delays for more complex interactions.

Videos by heise

Perspectives and discussion

The possible applications range from rapid prototyping and small helper apps to the vision of an AI operating system.

However, key questions remain unanswered: the stability, security, and reliability of an AI that executes code directly. According to Anthropic, Claude 4.5 is more strongly trained for security (alignment) and equipped with protective mechanisms against misuse.

While image generators such as Midjourney or DALL-E 3 produce media content, Anthropic is clearly aimed at software creation. This also distinguishes the approach from OpenAI's latest extensions, which are more geared towards general assistants.

Google's Firebase Studio is based on a similar concept. Users also design applications in the browser using voice commands, while seeing the results live in the same window. However, the tool is used to develop web applications and looks more like a WYSIWYG editor than a desktop.

Conclusion

Virtual desktops in the browser are not a new idea: Netscape founder Marc Andreessen was already experimenting with similar concepts in Java at the end of the 1990s. However, they never really caught on. Imagine with Claude now goes one step further and questions the principle of classic software distribution: programs are not installed, but generated ad hoc by voice input.

Even if it is only a short preview, the experiment provides a fascinating outlook – and is likely to further fuel the debate about AI-generated software.

(mma)