30 years of blue LED: The blue wonder

LEDs in all colors of the visible spectrum have long been part of everyday life. Three Japanese researchers were awarded the Nobel Prize for their work.

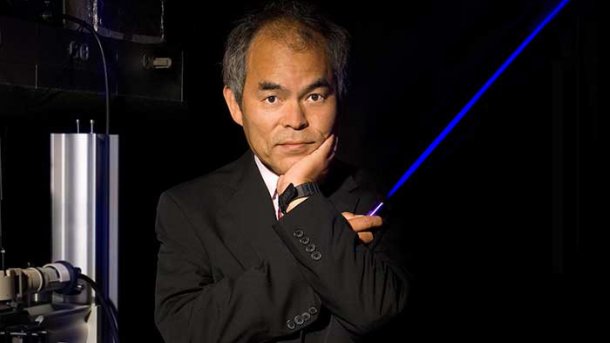

Shuji Nakamura, one of the three winners of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics, stands for a press photo with a blue laser model.

(Image: universityofcalifornia.edu; Randall Lamb)

The Volkswagen Group has been in a bad way before. It had rested on the success of the "Beetle" for far too long. With the first generation of the VW Golf and its notchback variant, the Jetta, the Wolfsburg-based company returned to the road to success in 1974. A technical detail of these vehicles: In the instrument cluster in the dashboard, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) instead of light bulbs indicated various operating states or problems as part of the model update. LEDs require less power and are almost indestructible. With incandescent lamps, on the other hand, it can happen that the indicator light and not the function that is actually being indicated is defective.

There was only one problem: blue was and is the standard signal color for high beams. But when the vehicles were launched, there were no usable blue LEDs – and red, green and yellow were the end of the color scale. Only with special permission was a yellow LED allowed to indicate high beam operation in VWs. It was not until 30 years ago that the first blue LEDs suitable for everyday use appeared, which today enable us to use economical and durable light sources, Blu-ray discs with capacities in the three-digit gigabyte range and possibly soon extremely durable and bright screens.

Blue LEDs were dim sparks

The road to success was riddled with setbacks. Henry Joseph Round, the personal assistant to radio telegraphy pioneer Guglielmo Marconi, had already discovered electroluminescence, i.e. the underlying effect, in 1907. The first practical light-emitting diodes were created in 1962 – at General Electric by engineer Nick Holonyak, who initially developed the red version, followed by green ones at Monsanto in the late 1960s. In 1972, M. George Craford, a former Master's student of Holonyak's, developed the first yellow LEDs. Along the way, he improved the brightness of the existing red and red-orange LEDs by a factor of 10.

(Image: Nobel-Komitee, Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

The next logical step was a blue LED, because white light can only be produced by combining the three primary colors red, green and blue (RGB) – as well as almost all color nuances found in nature. Each color screen displays colors by dosing RGB appropriately. The first functioning blue examples were created at the same time as the yellow LED based on magnesium-doped gallium nitride at Stanford University through the work of PhD students Herb Maruska and Wally Rhines. However, these LEDs were cloudy sparks, which is why they were of no practical significance. But it was clear where the journey had to go – no wonder that Japanese and American giants from the electronics, chemical and computer industries set about developing blue LEDs that were cheap to produce and sufficiently bright.

From waste product to light

The crux of the matter was to find suitable material for these LEDs. As the name suggests, LEDs are initially diodes, i.e. semiconductor components. Semiconductors are so called because they are made of material that is, in principle, electrically non-conductive. Through targeted contamination ("doping") with other substances, either an excess of electrons (n) or a lack of electrons (p) can be generated in them at an atomic level. If p-/n-layers are combined and a voltage is applied, current flows through them. Diodes usually consist of one p and one n layer. Their original tasks in electronic circuits are, for example, to protect against reverse polarity current sources or to rectify alternating current, as the current only flows through diodes in one direction.

If current flows from the n-layer to the p-layer, this releases photons, i.e. light. In conventional diodes, however, it remains in the infrared range and generates heat. However, if suitable semiconductor materials are combined, the waste product of the diodes, the photons, become the actual purpose: light. Conveniently, with the right choice of material, LEDs hardly heat up at all and are many times more efficient than incandescent lamps, where the brightness is only a side effect of the heat produced by the filament. In figures: An incandescent lamp converts only two to six percent of the energy supplied into light, an LED 50 to 70.

(Image: Philips)

The hour of Shuji Nakamura

So much for the theory. But it also says that the shorter the wavelength of the light to be generated, the more energy must be generated in the diodes at the band gap. In quantum theory, this is the energy difference between areas with different numbers of free electrons; in the case of the LED, in practice it corresponds to the area between the n and p layers where the photons are generated. The industry giants of the 1970s had cut their teeth on this gap and sunk millions into it.

Now it was Shuji Nakamura's turn. He graduated from the University of Tokushima in Japan (around 560 kilometers southwest of the capital Tokyo) with a bachelor's degree in 1977 and a master's degree in electrical engineering in 1979. He then joined the local chemicals manufacturer Nichia. Its main business at the time was phosphorus, which was used in picture tubes, among other things. Although Nichia also produced semiconductors for red and green LEDs –, it was competing with large corporations in this area. In 1988, Nichia's business was rather sluggish and the company lost money in the semiconductor sector. Nakamura was able to convince the Nichia owner to invest around 500 million yen (three million US dollars at the time) in the development of blue LEDs. Compared to the sums that the industry giants had previously sunk into the hoped-for blue miracle in vain, the three million was not much – but a failure of this investment would have meant ruin for Nichia.

Boss Nobuo Ogawa risked the money – whereupon Nakamura disappeared to the USA, to the University of Florida in Gainesville. At this point, it was already known that a prerequisite for an efficient blue LED was a crystal structure of the semiconductors used that was as perfect and highly pure as possible. Photons do not form at breaks in the pattern, but heat does. And in Gainesville there was a MOCVD reactor, a device for metal-organic chemical vapor deposition, a kind of high-tech vaporizer. It seemed suitable for producing these crystals.

No access without a doctorate

However, Nakamura did not have a doctorate at the time, which is why he was denied access to the reactor – and, by all accounts, his fellow researchers were anything but collegial. However, Nakamura was not discouraged by such adversities: he built his own reactor. After a year in Florida, he returned to Japan in 1989 with the aim of acquiring a MOCVD reactor for Nichia and continuing to experiment with it – and completing his doctorate. At that time, this was possible in Japan if you had published five scientific papers under your own name.

The desire for a doctorate turned out to be a sign of fate, as it was now known that two substances were promising candidates for blue LEDs: Zinc selenide (ZnSe) and – once again – gallium nitride (GaN), with which Maruska and Rhines were successful at Stanford in 1972. The majority of researchers focused on zinc selenide because it was easier to produce the required high-purity crystals – but only as n-semiconductors. This was not the only reason why Nakamura considered GaN to be more promising: as numerous scientists and engineers were already researching ZnSe-based LEDs, Nakamura saw little chance of publishing five papers for his doctorate in this field.

But Nakamura had little to be optimistic about. Initially, it was not possible to produce p-type semiconductors from GaN. Nevertheless, Nakamura was not alone. As early as 1986, Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano at Nagoya University had succeeded in growing high-purity n-GaN crystals on an aluminum nitride layer applied to a sapphire substrate. In 1989, they had also managed to grow p-type – because they had accidentally discovered that their p-type layers behaved like semiconductors when they had previously been scanned by the beam of a scanning electron microscope. The sum of their experiments culminated in 1992 in the presentation of a brilliantly bright blue LED. Once again, a milestone, but blue LEDs could not be mass-produced on this basis.