MSX: When Sony, Philips, Samsung and Microsoft cooperated to build computers

In 1983, the software company Microsoft, together with ASCII from Japan, decided to create a standard for home computers. Many well-known names joined in.

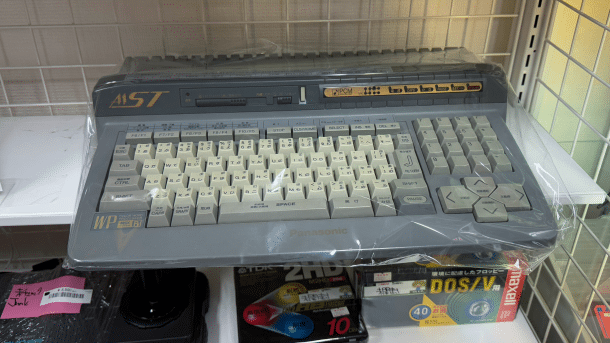

Panasonic MSX turbo R: The penultimate MSX computer ever. Today worth thousands of euros due to its rarity.

(Image: Ben Schwan)

A narrow staircase leads down to the retro paradise: In Tokyo's Akihabara district, you have to know exactly where you're going. It's my second visit to this mecca of old computing technology; I was here once before in 2018. Everything seems a little less tidy and rather empty to me, which could also have something to do with the fact that the trend of being interested in old gaming and computer systems has boomed in recent years. However, this has also meant that prices have risen immeasurably, and it's often easier to find things online than locally.

Anyway, I'm only there to touch, admire and smell. And right at the back in the corner is something that I would probably have given half a leg for as a teenager: a Panasonic FS-A1ST, nicely wrapped in cling film. It was the penultimate MSX computer ever to go on sale in 1990, albeit only in its home market of Japan. Nevertheless, I knew a few people who had proudly imported the machine to Germany for 1000 DM plus, of course with a suitable power supply adapter from 100 to 230 volts. My goodness, I was jealous back then.

An almost forgotten standard

MSX? What is MSX, please? Didn't we have Commodore C64, C128, later Amiga, Atari (from 800XL to ST, I'm summarizing eras here in fast-forward) and co. in the mid-eighties to the beginning of the nineties, before the Windows wave started? Maybe a Schneider CPC, a Sinclair ZX Spectrum or an Apple II? With rich parents, a Macintosh?

(Image: Ben Schwan)

MSX stands for “MicroSoft eXtended”, according to later statements by Kazuhiko Nishi of the Japanese ASCII Corporation (which had since become a Microsoft subsidiary), considered the father of the standard, also for “Machines with Software eXchangeability” or the names of the two first hardware manufacturers, Matsushita (Panasonic) and Sony. It was an interesting attempt by large, mainly East Asian electronics companies to jointly conquer the home computer market by agreeing on a common platform. The list of participants reads like a who's who of major brands, many of which still exist today. Sony was there, Philips from Holland, Yamaha, Panasonic/Matsushita, Sanyo, Sharp (albeit only in Brazil), JVC, Mitsubishi, Toshiba, Hitachi, Canon, Casio, Pioneer, Yashica (subsidiary of Kyocera) and Fujitsu. In South Korea, Samsung, Daewoo and GoldStar (today: LG) participated, in Italy Fenner.

Nishi is said to have had the idea for MSX during a visit by Bill Gates to Japan. Or, if Wikipedia is to be believed, Microsoft first, which Nishi then joined. In any case, the idea quickly met with approval in the electronics industry. They wanted to be stronger together, not work against each other. A frame design from Spectravideo, which Nishi had seen in Hong Kong, helped. It was decided to use the Z80A from Zilog with 3.58 MHz as the CPU, partly because CP/M could already be run on it. An agreement was reached on a graphics chip from TI (later: Yamaha), a sound chip from General Instrument and the interfaces including so-called cartridge slots for game modules and hardware expansions. All computers had the same MSX BASIC from Microsoft, whereby manufacturers could distinguish themselves with add-ons such as additional software integrated in the ROM.

Four MSX versions, only two of which we have

MSX was available in a total of four incarnations. MSX 1 (or simply: MSX) was released in Japan and Europe in 1983, the USA was largely left out (except for Spectravideo machines). MSX 1 had the most support, the countless consumer electronics companies obviously felt as if they were establishing a new VHS (the standard format for video cassettes established years later) – only for home computers. From today's perspective, MSX 1 is quite special and feels old-fashioned, as the graphics still had problems with the color transitions and other difficulties. People still tended to save programs to cassette if they were not available as cartridges, which required a lot of patience. Some games look as if they were made for the ZX Spectrum, but this was only because it was easy and cheap to port from this platform, including the very special graphics. The CX5M from Yamaha was very exciting in the MSX-1 segment: the machine had a MIDI interface, which was very rare at the time – before the Atari ST –. It became an insider tip in music circles.

Videos by heise

The second standard version, MSX2 followed in 1985. The graphics were improved, floppy disk drives became the norm, there were special systems for streaming video (Genlock) and the graphics improved. Although the systems were 8-bit computers with the same old Z80A, their multimedia capabilities put them somewhere between the C64 and Amiga, at least for fans, minus the graphical interface. In addition, thanks to MSX-DOS you could even read MS-DOS files from the PC, Microsoft made it possible. MSX2+ with better graphics (19268 colors at the same time!) and better sound (MSX Music with FM sound) followed in 1988. By this point, however, the caravan of major manufacturers had already moved on, and not a single machine was launched on the market in Europe. Sanyo, Sony and Panasonic stuck with it in Japan, however.

(Image: Ben Schwan)

Business continued to go well there, thanks in part to the many games from countless well-known studios. There was even a dedicated online gaming service called THE LINKS. Konami debuted series that are still popular today, such as “Metal Gear”, on MSX. There were titles such as “Dragon Quest” or “Final Fantasy”, “Vampire Slayer” and many more for MSX, in wonderfully detailed pixel graphics. The last rebellion of the standard, the MSX turbo R, with which only Panasonic/Matsushita dared to make a new start from 1990, was consequently also a purely Japanese phenomenon. This very interesting machine had an R800 RISC chip installed, which was Z80A-compatible but could also switch to a proprietary mode with no less than 29 MHz.

Computer love in the eighties

I came to MSX by chance. An electronics enthusiast relative had brought me the computer from a wholesale store where it was on sale. It was an MSX 1 from Sony's “HitBit” line, an HB-75D (the “D” stood for German keyboard, of course). The 1984 machine had 64 GB of RAM and a connection for a cassette drive, a great cursor pad on the right for gaming and was finished in chic black with gray and red accents.

It was a machine made for young computer enthusiasts, complete with an easy-to-understand manual with typical Japanese charm. The integrated BASIC from Microsoft was much better than the annoying POKErei you had to do on a Commodore. I got my first games on cartridges from Konami, which you inserted into one of two slots. Later, I got a Game Master, a second cartridge that you inserted at the same time as a game and which then unlocked cheats and Easter eggs. I spent countless afternoons playing “Nemesis” and its successors, “Penguin Adventure” and “F1 Spirit”. I typed dozens of pages of listings so that the machine would play a current hit with the not really good original sound chip (unfortunately much worse than that of the 64) or invite me to a round of spaceship shooting.

(Image: Ben Schwan)

The MSX1 from Sony was followed by an MSX2 from Philips. This had a built-in 3.5-inch floppy drive and the aforementioned better graphics. My last MSX was a Sony MSX2, albeit second-hand and with a DIN connector for the keyboard that was always loose, which I soldered together myself. As MSX was not widely used in Germany despite the well-known brand names, there was a nationwide network. There were also MSX fans in Switzerland and especially in Holland. Hobbyists and importers were active early on, procuring a lot of material from Japan, be it exciting magazines or (especially, of course) games. Getting to know other people who had MSX, things that you had never seen before was always exciting for everyone involved. And many MSX fans also developed an early love of Japan, even before the hype surrounding anime and manga was known in this country.

The standard lives on (a little)

Anyone who wants to get involved with MSX today has plenty of opportunities to do so. In addition to collecting the hardware itself, which can be quite expensive (see below), there are countless locally running emulators. JavaScript-supported web emus such as FileHunter, which include many of the biggest MSX hits and run completely installation-free in the browser, are a good place to start. For example, “Quarth” and “Space Manbow” from Konami, “Columns” from Sega or “Gorby's Pipeline” from Compile are really great, to name just a few random examples. “SD Snatcher” is an absolute Konami classic that unfortunately almost nobody knows.

(Image: Ben Schwan)

But you can only get the right dose of MSX with real hardware. However, you should only buy used MSX computers (unless you have a passion for tinkering) if they have been looked after and, if necessary, refurbished. If they come from Japan, you will need a power supply converter. Typical retro computer problems such as leaking electrolytic capacitors that require recapping, drive belts that crumble or discolored housings are common. And you also need the right change for more specialized models. For example, Japanese dealers are currently selling the very last MSX from Sony, the MSX2+ system HB-F1XV from 1989, in adequate condition for almost 1800 dollars. For Panasonic's FS-A1GT, the second and last MSX turbo R (and therefore the very last MSX computer ever) from 1991, a whopping 4000 dollars is being asked for on eBay.

And the hobbyist scene is still going strong. On platforms such as MSX.org and at conferences such as the MSX2 GOTO40 (this year in Holland in the fall), tinkerers, developers and other freaks who have by no means given up on the MSX standard, connect modern hardware, translate games and much more gather. MSX father Nishi also remains active. He has been dreaming of MSX 3 for several years.

(bsc)