De-globalisation: Can Europe supply itself with copper?

In our raw materials series, we look at the extent to which Germany and Europe could free themselves from import dependencies. What about copper?

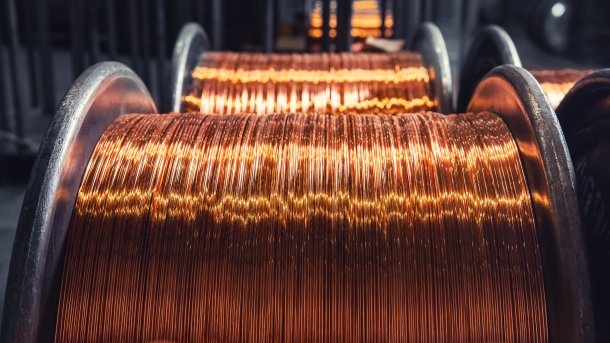

(Bild: Shutterstock)

(Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version des Beitrags)

One of the oldest copper smelters still known to mankind was located in Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan in present-day Jordan. Already 6,000 years ago, large quantities of copper were extracted there from the ores of a nearby mine. The Egyptians made weapons, tools, jewellery and household appliances from the metal. Knowledge about the use of copper spread quickly. Many new applications led to copper being traded on the stock exchanges in London and New York as early as the 19th century. There were also many smaller copper mines in Germany, but as early as the 1920s, before a trading centre for copper was founded, those responsible had to admit to themselves that they were "economically dependent on the large North American producers".

The dependence still exists today, but the use of the metal has changed completely. Copper has very good electrical conductivity, which is why 79 percent of production ends up in this application area. Copper is needed for cables to transport electricity and data in the nationwide infrastructure and inside buildings, it is in transformers, electric motors and cable harnesses. The German Raw Materials Agency expects demand to roughly double by 2035. The main drivers of this development are the expansion of the power grid, electric motors for cars, wind energy and solid-state batteries.

Shenzhen, Yantian Port

(Bild: zhangyang13576997233 / Shutterstock.com)

The past months have painfully shown that dependence on resources comes at a high price. But can the wheel still be turned back? So let's take a look at the supply situation.

How far Europe could supply itself with strategically important raw materials and what that means for industry is what we want to explore with a raw materials article series.

- New Series: De-Globalisation - How Independent Can Europe Be?

- De-globalisation: Can Europe supply itself with lithium?

- Rare earths and platinum group metals: Can Europe be self-sufficient?

- De-globalisation: Can Europe supply itself with steel and aluminium?

- De-globalisation: Can Europe supply itself with copper?

Exploration of copper deposits in Germany

Germany still plays a role internationally in copper production and processing. 16,000 people work in this industry, even though there is no longer any copper mining in this country. At the turn of the millennium, the last mines were closed, they were no longer profitable. That could change: When the world market price for copper rose rapidly in 2007, the authorities in Brandenburg and Saxony approved the exploration of the Spremberg-Graustein-Schleife copper deposit near the Polish border. On the Polish side, copper has been mined for years in Europe's largest copper mine. The German share lies more than 1,000 metres deep and is estimated at 1.5 million tonnes of copper metal. Internationally, this is little. In 2018, more than 20 million tonnes were extracted worldwide, and Chile's largest mine alone supplies more than one million tonnes per year from a low-cost open-cast mine.

The extraction from the mines has to be processed in several steps. The rock is first ground, chemicals then separate the copper-rich ore from the rest and enrich it into a concentrate. Some mining nations supply ores, others only the concentrate. To obtain pure copper, the concentrate is melted in blast furnaces and finally purified in electrochemical electrolysis processes. This process mostly takes place in the countries that also process the copper. In 2020, Germany imported about 1.2 million tonnes of copper ores and concentrates and processed them into raw copper. Globally, the Federal Republic ranks fourth among importing countries and copper producers behind China, Japan and South Korea. The main German suppliers were Peru, Brazil and Chile. The South American countries and Australia also have the largest raw material deposits. Five of the ten largest copper mines are located in Chile.

Who drives copper demand

The European copper balance is not as bad as for other metals. Europe-wide, about four million tonnes of copper are needed, almost two thirds of which come from our own resources. At 43 percent, the recycling share from domestic and industrial scrap is quite high, as it can be recycled and processed into new products an infinite number of times without any loss of quality. Another 20 per cent is extracted from European mines. Europe also has a certain independence in terms of imports due to a large number of suppliers. Twelve percent of copper demand is imported as purified metal, 25 percent as ore or concentrate. The German company Aurubis AG is Europe's largest copper producer and an international leader in copper recycling.

But the situation in the copper market differs significantly from other metals in one respect. Since 2002, China has been the driving force behind demand. In 2019, China processed 12.7 million tonnes of copper, which is slightly more than half of global production. But the Chinese are far from able to meet the demand from their own production. They had to buy more than 22 million tonnes of copper concentrate on the world market in 2019. That is why the European copper import ban cannot do much to a raw material exporter like Russia. The Russian ore now goes to China.

China pushes into the copper market

But China is finding it difficult to exert a major influence on the global copper market. Because the metal has been used on an industrial scale for a long time, the mining rights for the large deposits are coupled with decades-long contracts that are mostly held by Western companies in a market that has grown historically. China has to buy in there with a lot of money or build its own mines that exploit smaller copper deposits. Since the late 1990s, the country has gone both ways. China has brought mines into production in the African states of Congo, Zambia, South Africa and Eritrea, as well as in Laos, Myanmar, Australia and Peru. During the global financial crisis, the country took advantage of the economic problems of some mine operators and bought mining licences in Peru, Afghanistan and Ecuador. This financial support enabled Peru and Congo to become the world's most important mining countries for copper.

Europe nevertheless retains a large access to the mines. So far, no Chinese company has managed to make it into the list of the ten largest companies. They are based in Chile, Switzerland, Australia, the USA, Canada, the UK, Poland and Russia.

The upcoming issue of the MIT Technology Review also deals with the topic of deglobalisation. In various texts, we explore the question of the extent to which it is possible to reverse processes of deglobalisation. The new issue can be ordered in the heise shop from 28.9. and will be available in stores from 29.9.

(jle)